Debbie Sorkin, National Director of Systems Leadership at the Leadership Centre, shares her thoughts on the Messenger Review of health and social care leadership, highlighting some of the encouraging recommendations as well as aspects where the Leadership Centre would part ways with the findings.

On the back of The Art of Change-Making, our compendium of approaches for leading and managing effectively in complexity, there’s a quotation from Leonardo Da Vinci: “Learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else”. From a Leadership Centre perspective, it’s gratifying to see the Messenger Review of health and social care leadership, Leadership for a collaborative and inclusive future, making some connections.

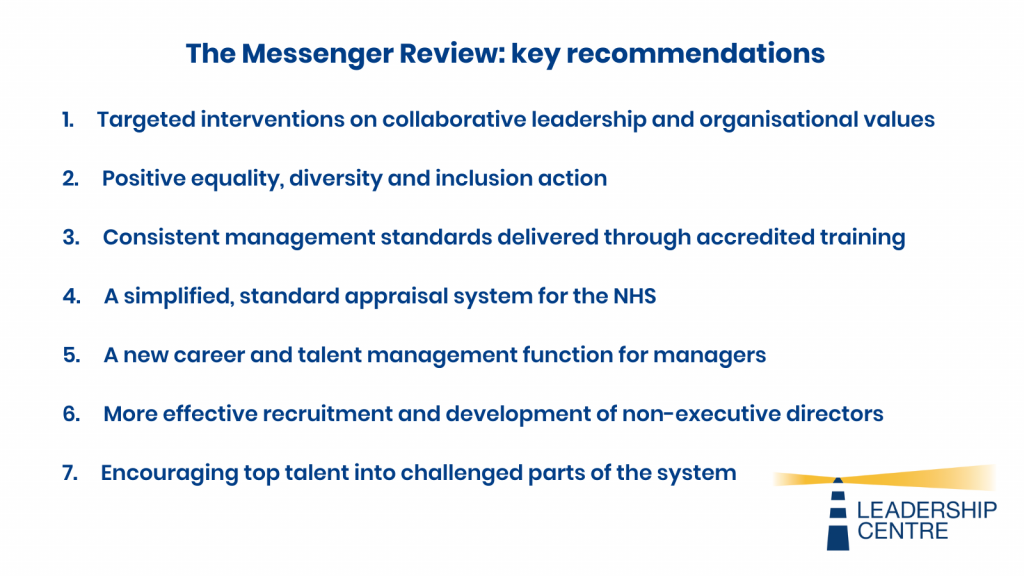

The Review was commissioned by Secretary of State for Health Sajid Javid, and led by General Sir Gordon Messenger, a former vice chief of defence staff, and Dame Linda Pollard, chair of Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, with a review team comprising staff from the NHS and the Department of Health and Social Care. It was published last week, with seven core recommendations.

One of the recommendations focused on the need for leaders at all levels to be able to work effectively across boundaries, reflecting the move towards Integrated Care Systems. Hence the recommendation for more targeted interventions on collaborative leadership. At the same time, the authors acknowledge the centrifugal pull of traditional cultures away from collaboration: “…the current cultural environment tends to be unfriendly to the collaborative leadership needed to deliver health and social care in a changing and diverse environment. The system is undergoing a fundamental change from a competitive to a collaborative ethic, and behaviours need to reflect this.” Hard to disagree: much of the Centre’s work over the last decade, from the national systems leadership programme Systems Leadership – Local Vision to our current work supporting Integrated Care Systems, has focused on bringing people together to work differently and shift cultures from within.

We are also pleased to see an emphasis on actions and behaviours, rather than focusing on a single system leader, even if the system did not currently reflect this: “Every opportunity must therefore be taken to embed [collaborative leadership] behaviours so that they become institutionally valued and instinctive to all…owned and driven by the leadership at all levels…”

Again, this tallies with our approach: we describe systems leadership as “the collaborative leadership of a network of people, in different places and at different levels, coming together on the basis of a common purpose and co-operating to effect significant change”. And we particularly welcome the idea of embedding behaviours as a means of improving equality, diversity and inclusion, not least in the light of the recent Royal College of Nursing studydescribing racism as ‘endemic’ in health and care, with white NHS nurses twice as likely as black and Asian colleagues to be promoted.

Thirdly, the review contains a welcome acknowledgement of the impact of politics, and of how pervasive, and damaging, that impact can be, creating an instinct “to look upwards to furnish the needs of the hierarchy…[having] an impact on behaviours” and leading to blame cultures and responsibility avoidance. The Leadership Centre was set up precisely to improve leadership in political environments, and the people on our programmes, or at our events, will commonly be working in local or national government; in national bodies such as the emergency services; or in highly politicised environments such as the NHS.

But there are areas of the review where I think we would part ways. Firstly, the report has little to say on how you do this in practice: for example, the review states: “We found no consistent view of principles for collaborative systems leadership; current models extol the virtue of certain behaviours but lack a structured framework.”

Perhaps we should have been more forceful in our approach, because there are two frameworks that describe behaviours in very practical terms, for people at all levels: the national and international research study Exceptional leadership for exceptional times, and the Leadership Qualities Framework for Adult Social Care, which in turn maps across to the behaviour framework for the NHS produced by the NHS Leadership Academy. This reflects an approach that I’ve found all too often in the NHS: discarding or not noticing what you’ve got, and going for something new, rather than using what you’ve got that’s ‘good enough’ to bed in behaviours over a number of years.

That leads on to my second gripe. The review is nominally about health and social care. And it recognises the lack of parity of esteem between the sectors, calling it “a blight on effective collaborative working”. But any focus on social care – and primary care, come to that – fades to a Cheshire Cat grin over the course of the report, and it has little to say about how to remedy the issue in terms of leadership and management development (to be fair, it seems as if the original intention was to look into this in greater depth). Had the review looked more at social care, it might even have found lessons from the sector in how to make collaborative leadership a reality.

And in the end, the review can’t resist the allure of the heroic leader, calling for greater incentives for ‘the best’ leaders and managers to take on more difficult roles. But the reason the roles are so difficult is systemic: as the NHS Confederation stated in their own briefing on the review: “No amount of heroic leaders can make a system work which is overwhelmed with demand and dealing with more than 100,000 vacancies”. Rather than waiting for the heroic leader to come along, what we are looking to imbue in the people we work with, particularly in the “squeezed middle” is a sense of agency for themselves, leading ‘along’ and connecting with others from outside the NHS, rather than waiting for permission or direction from above.

There is a wider point, as well. Is the overall framing – i.e. leadership of health [NHS] and social care (local government/independent sector) really about institutions, or sectors, and their leadership? If what we’re really bothered about are health inequalities, whether evidenced in deprivation or waiting times, then a better question might be how we bend leadership (all the leadership of a place) beyond better/more effective collaboration, to develop a shared vision and purpose focused on understanding system complexity, with a view to giving every community (remember levelling-up?) a chance to thrive.

So, what happens next? Looking at the number of leadership reviews in the NHS in the recent past, the answer isn’t encouraging. Some commentators have been scathing: Alastair McLellan, editor of the Health Services Journal, has described the review as ‘a con’ and ‘a triumph of media spin’: “this gratuitously over-sold, inoffensive memo fails to get anywhere close to most of the issues managers have to address…at least our expectations have now been appropriately lowered.”

But from a Leadership Centre perspective, perhaps this is looking in the wrong place for leadership. We always ask the question of people in their places: “What can you do? What small, practical, do-able thing can you do to connect with others and make a bit of progress, on gnarly and complex issues, in your system?”. It probably won’t merit a press release or a bevy of commentaries. But it will have the benefit of being real: shifting the culture, and moving the system, one action at a time.